Tune In’s take on Paul’s “Uncool” Musical Tastes

NOTE: The purpose of this analysis is not to exaggerate the severity of John’s onstage behavior which could have (at least occasionally) been conducted in good fun and camaraderie. The object is to determine whether or not Tune In is capable of presenting John’s disruptive and/or undermining behavior objectively in a way that allows the reader to judge the appropriateness of such behavior.

–//–

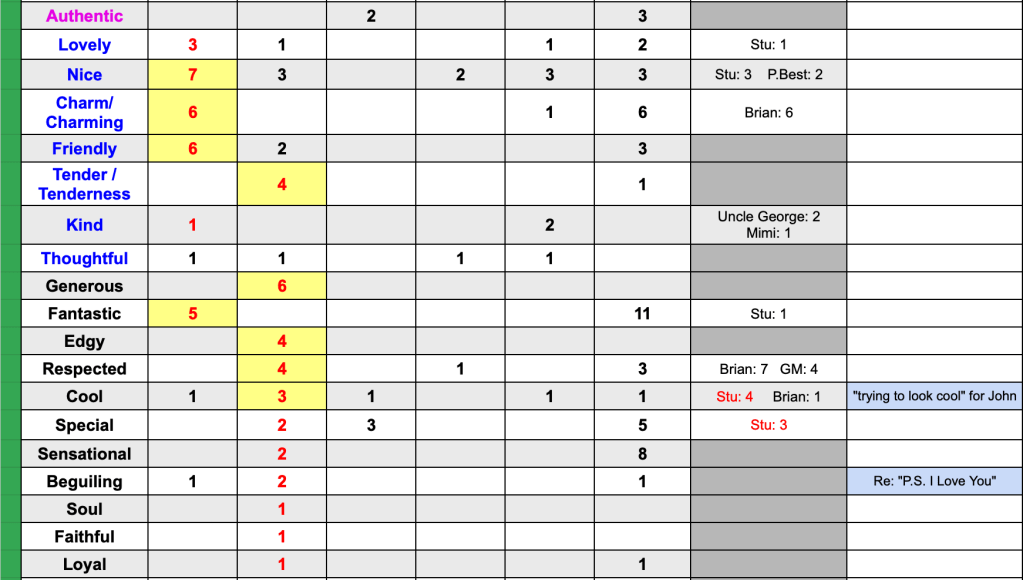

Multiple times throughout the book, Lewisohn writes with seeming approval about John undercutting Paul’s “soft” songs or musical tastes.

Here are five examples of this happening live, onstage:

On page 614, Lewisohn tells us how “Paul would flutter his eyelashes when he sang certain songs,” and calls “Somewhere Over the Rainbow” “one of [Paul’s] flutter numbers, guaranteed to go down a storm with the girls.”

Tune In describes John teasing Paul onstage: “John pointed to Paul, burst into raucous laughter and shouted, ‘God, he’s doing Judy Garland!’ Paul had to keep singing in the knowledge that John was pulling crips and Quasis behind his back or making strange sounds on his guitar to interrupt him.”

Of this, Lewisohn writes, “There were always several simultaneous reasons why an audience couldn’t take their eyes off the Beatles.”

About “Besame Mucho,” we get a quote from Lindy Ness: “When Paul sang ‘Besame Mucho,’ John used to stand behind him and make cripple faces. He had to: Paul was asking for it.” (p761).

During “A Taste of Honey,” John interrupts Paul’s performance by yelling at the audience. Lewisohn calls this behavior an example of “the Nerk Twins’ chemistry” (p1178).

When Paul sings “Till There Was You,” “[John] speaks most of the lines in a persistent piss-taking echo: ‘No, I never heard them at all’ (‘No, he never heard them’)” and Lewisohn writes, “[Paul’s] not even necessarily cross about it—he knows it’ll happen because this is John, and John is his fairground hero.” He also writes, “It’s part of the double-act, one among so many reasons they’re special together” (p1178).

Also about “Till There Was You”: “John really had a go at Paul for singing this—but didn’t try to stop him doing it, recognizing there was scope for all kinds of music in this group, to please all kinds of audiences” (p615).

Does it sound like John is preoccupied with projecting a “cool” image? We think so. Perhaps his undermining behavior garnered the praise and approval of a few (like Lindy Ness), but it could hardly be described as supportive of his partner (or reflective of good “leadership”).

And yet, Tune In always assures us that John is being awesome. Sometimes even a “hero.”

Instead of dispassionately framing John’s behavior as immature or insecure upstaging, Lewisohn calls John’s attention-seeking antics a part of John and Paul’s “chemistry,” which is “special” and a “[reason] why an audience couldn’t take their eyes off the Beatles.”

And, of course, we hear once again that John is Paul’s “fairground hero.”

Somehow, by mocking Paul doing his “flutter numbers” John is “recognizing there’s scope for all kinds of music.”

Note that, according to Tune In, Paul himself isn’t recognizing scope by choosing and singing the songs (even in the face of mockery); John is recognizing scope by allowing him to do it (while simultaneously making fun of him for it).

Our final example is one where John doesn’t even allow Paul to finish his performance, and Tune In uses this to pay John the biggest compliment yet.

Regarding the Beatles’ live performance of Elvis’s hit single “Are You Lonesome Tonight”, only days after its release:

“Paul set down his guitar, clasped the microphone and did his Elvis act, the great solo star crooning his new slow one. It was already going to pot when he went into the long spoken-word middle section about ‘all the world’s a stage,’ which he’d crammed into his brain inside a few hours … and then John just stopped the group dead.

Refusing to be involved in anything so corny, John completely took the piss out of Paul, ripping his close mate and bandmate to shreds in front of everyone. ‘They sent me up rotten,’ Paul says, ‘especially John. They all but laughed me off the stage.’”

So from this description and Paul’s quote, we can surmise that the Beatles had rehearsed and prepared the number, “spoken-word middle section” and all. Why then, did John not object to the corny, spoken-word interlude during rehearsal? Assuming John’s mid-performance “piss-take” was not a comedy routine pre-planned by all the Beatles, this anecdote suggests that John knowingly set Paul up for public ridicule and relished the opportunity to pull the rug out from under him onstage.

To be clear, this would be a perfectly fine choice if Paul was in on the joke and consented to the bit. But deliberately setting Paul up to fail is unambiguously un-cool.

Nevertheless, here’s how Tune In justifies John’s behavior:

“This was the way John dealt with things, and he also knew the Beatles must have a solid front line, not back a soloist. As he said, ‘Every group had a lead singer in a pink jacket singing Cliff Richard-type songs. We were the only group that didn’t … and that was how we broke through, by being different’” (586).

There’s no reason to connect John’s quote about “being different” to this anecdote (the footnote indicates his quote is taken from a December 1969 interview called “Pop Goes the Bulldog”) except to spin John’s behavior in the noblest way possible.

Paul wasn’t trying to be “a lead singer in a pink jacket”—he was merely taking the lead vocal just as John and George did in their turn. Did John also stop the band dead in the middle of his own solo spots, in order to ensure they kept a “solid front line” that would allow them to “[break] through by being different”? Of course not. John is simply covering his embarrassment here, insecure about perceived softness, and seeking negative attention.

(For readers who may think we’re overblowing this topic, imagine for a moment if Paul was doing this to George Harrison onstage. Would Paul’s behavior be praised?)

It’s outrageous for Lewisohn to spin John’s every behavior into something awesome (“audiences couldn’t take their eyes off”; “fairground hero”), visionary (“we broke through by being different”), egalitarian (“solid front line”) broad-minded (“recognizing there was scope for all kinds of music”), and indicative of a GOOD PARTNER, actually (“part of the double-act”; “Nerk Twins’ chemistry”; “special together”).

Meanwhile, Paul is “asking for it” by doing “flutter numbers” “guaranteed to go down a storm with the girls,” “making his eyes big,” being “so corny,” and trying to be “the great solo star,” like a Cliff Richard knockoff “in a pink jacket.”

Does this portrayal look even-handed?

—//—

FULL EXCERPTS:

“[‘Are You Lonesome Tonight’] came out in Britain on Friday, January 13, and they did it the next night at Aintree Institute. Paul set down his guitar, clasped the microphone and did his Elvis act, the great solo star crooning his new slow one. It was already going to pot when he went into the long spoken-word middle section about ‘all the world’s a stage,’ which he’d crammed into his brain inside a few hours … and then John just stopped the group dead.

Refusing to be involved in anything so corny, he completely took the piss out of Paul, ripping his close mate and bandmate to shreds in front of everyone. ‘They sent me up rotten,’ Paul says, ‘especially John. They all but laughed me off the stage.’ This was the way John dealt with things, and he also knew the Beatles must have a solid front line, not back a soloist. As he said, ‘Every group had a lead singer in a pink jacket singing Cliff Richard-type songs. We were the only group that didn’t … and that was how we broke through, by being different’” (586).

—//—

“We always requested Paul to sing ‘Long Tall Sally.’ He used to say, ‘I can’t do it because it kills me throat,’ but then he would. He’d announce, ‘I’m doing this one for these two flossies over here,’ or something like that. Girls used to say his eyes were like mince pies. He had long eyelashes and would deliberately flutter them, and though you knew he was always aware of himself, he was so friendly to everybody that you couldn’t help but like him.’

—BERNADETTE FARRELL

One of the flutter numbers was ‘Over the Rainbow,’ guaranteed to go down a storm with the girls. The song from The Wizard of Oz seemed a strange choice, but the Beatles considered it valid because Gene Vincent did it. Paul sang it somewhere between the two versions, pausing impressively after the heightened ‘Somewhere’ and then sweetly rolling down. Cavern girls would get used to the sight: he made his eyes big, turned his face up and slightly at an angle and fixed his gaze above their heads on a brick at the far end of the center tunnel.

Sometimes John joined in with fine harmonies, but mostly he took the piss. Pete says that during one Cavern performance of ‘Over the Rainbow,’ John leaned back on the piano, pointed to Paul, burst into raucous laughter and shouted, ‘God, he’s doing Judy Garland!’ Paul had to keep singing in the knowledge that John was pulling crips and Quasis behind his back or making strange sounds on his guitar to interrupt him. Yet, if Paul stopped in the middle of the number, John would stare around the stage, the essence of innocence. There were always several simultaneous reasons why an audience couldn’t take their eyes off the Beatles.

Paul took such behavior from no one but John, but also he gave it back and was strong-minded enough to carry on doing what he wanted, knowing how much the audience liked it. He sang these songs well, and added one more to the portfolio at this time, the Broadway show number ‘Till There Was You,’ as covered in a new version by Peggy Lee—or Peggy Leg, as Paul called her. (He was given her record by his cousin Bett Robbins.) John really had a go at Paul for singing this—but didn’t try to stop him doing it, recognizing there was scope for all kinds of music in this group, to please all kinds of audiences … just so long as no one went near jazz” (614-15).

—//—

“LINDY NESS: ‘When Paul sang “Besame Mucho,” John used to stand behind him and make cripple faces. He had to: Paul was asking for it. But John wasn’t particular—he also took the piss out of George and Pete, mostly by imitations of some kind’” (761).

—//—

The tape throws great light on the Nerk Twins’ chemistry. While Paul is singing ‘A Taste of Honey,’ John suddenly shouts ‘SHUT UP TALKING!’ to someone in the audience, interrupting Paul much more than the chatterbox. Paul knows this, and is pitched into laughter. When he sings ‘Till There Was You,’ John—just a beat behind—speaks most of the lines in a persistent piss-taking echo: ‘No, I never heard them at all’ (‘No, he never heard them’). Paul chuckles and plows on; he can’t stop it, and he’s not even necessarily cross about it—he knows it’ll happen because this is John, and John is his fairground hero. It’s part of the double-act: the audience try to watch the singer but can’t tear their eyes off his mate, who’s probably also pulling crips. John couldn’t do this to anyone else without risking a thump, Paul wouldn’t accept it from anyone else; Paul gets to sing his song, John gets to undermine him. It’s just one facet of the complex sibling relationship they’ve always had, one among so many reasons they’re special together” (1178).